It’s been a couple of weeks since Robin Williams died. I’ve written a lot about suicide and suicide prevention during that time, and there’s been a lot of discussion in the public forum about suicide and what we can do about it. This is really good. We’re making progress on turning suicide into something people can talk about.

Those of us who work in suicide prevention, intervention, postvention, and research have an obvious leadership role for starting and guiding those conversations. We’ve learned a lot about what works, and we’re also learning how to talk about suicide openly. People (rightly) look to us for help in knowing what to think.

I’m concerned about some of what we’ve chosen, as a field, to say. I’m worried that, in preaching the gospel of what we’ve learned about suicide, we’re alienating more potential allies than we recruit. I’m worried that we may be choosing battles that end up losing ground in the larger fight.

As an example, please check out this opinion piece in CNN, written by Bill Schmitz, Jr., current President of the American Association of Suicidology. It came out on August 14th, three days after Williams’s death.

These are my main concerns:

- It sharply rebukes The Academy and the grieving people who forwarded the tweet of the genie from Aladdin

- It blames Williams and, effectively, perpetuates the stereotype of calling suicide a selfish act

- It criticizes media for failing to follow our (somewhat obscure) guidelines rather than encouraging them to partner with us in future

- It denies the lived experience of people with mental illness who find treatments ineffective

Much of what appears in Schmitz’s piece is good, and I want to be clear that I’m not saying he shouldn’t have written it. (Bill, if you’re reading this, I particularly appreciate that you chose to share some of your personal story and reactions even though you were speaking from your official position as AAS President. I think human stories are really valuable in helping people to process and hear our official recommendations.) I believe that all of the people who’ve written suicidology perspectives have done so out of good intent, and I want to make sure I start by saying that.

My point is that I think that piece, and others like it, didn’t play very well outside the suicide prevention community. The way we chose to frame our recommendations and comments had some problems, and that’s what I want to talk about. I think we can do an even better job next time. I think we can still say the important things about safety and prevention without pushing people away and shaming our potential allies.

The “Genie, be free” tweet

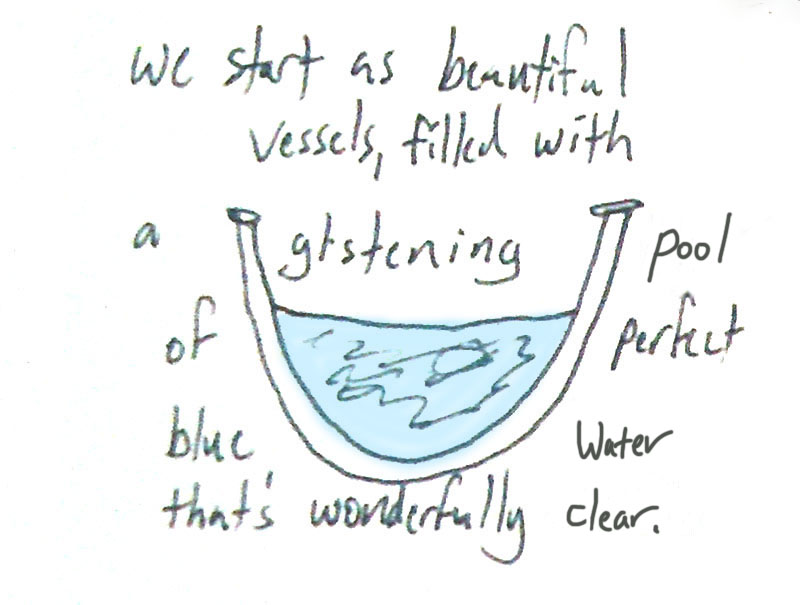

First, the line in The Academy’s tweet, “Genie, be free”, is a direct quotation from Aladdin. The genie was one of Robin Williams’s most-loved roles, and I know—because people told me—that the tweet helped a lot of them feel a sense of closure about Williams’s death. It was comforting to them.

In the film, it’s a scene when Aladdin frees the genie from the lamp in which he’s been imprisoned for years. It is a literal and metaphorical unshackling of the spirit, a hand extended to release a tormented spirit from bondage.

Should we be surprised that people found it a compelling message for talking about Williams’s death by suicide? I know the media guidelines suggest that we not talk about suicide as an escape or a way to get out of pain (Schmitz writes “Suicide should NEVER be presented by media as a means to resolve or escape one’s problems“), but I also know that many of the suicidal people I’ve talked to in 15 years on the suicide hotline do think of suicide that way. We can talk about ways that viewpoint can hinder suicide prevention efforts, and we can talk about ways to shift the dialogue, but I think that we’re denying people’s lived experience if we expect them to completely extinguish the “freedom” concept.

I’ve been to a lot of funerals lately. People say, overwhelmingly, that the person who died is “in a better place now”. Isn’t that basically the same message as The Academy’s tweet? People try to make the best of it when someone they loved has died, and I think we’re treading on thin ice if we expect people to behave in a radically different way when someone dies by suicide.

If there’s research supporting the idea that portraying suicide as freedom or escape in the media tends to increase suicide deaths, let’s talk about that. Let’s give people suggestions for what to do instead.

But calling people out for getting it wrong makes enemies for us, and given that most people seem to have found the tweet comforting, I think it runs the risk of painting us as out-of-touch academics muttering about a tempest in the proverbial teacup.

Put differently, calling out the Academy is a war of choice. We’re on totally solid ground to pick that fight, but I don’t know that it was good strategy. It irritated people (many of them just regular folks who read CNN) without gaining much ground.

Effectively calling Williams selfish

I’m really bothered by the line in Schmitz’s article that includes this parenthetical:

“(contrary to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ twitter post, the genie is not free, the genie’s pain has now been dispersed to a very large audience).“

The genie’s pain has now been dispersed to a very large audience. Yep, that’s true. So what?

The argument seems to be that, by killing himself, Robin Williams shared his suffering with a huge number of people across the world, effectively traumatizing them and exposing them to risk. Because Williams was so well known, his death—by any means, not just suicide—was bound to be big news. Celebrity deaths always touch a lot of people. And therefore, Robin Williams should not have killed himself.

But the thing is, Robin Williams didn’t really have any choice about whether his death would be big news. It wasn’t under his control. If you’re a celebrity, people write stories about you.

I feel like this kind of statement is, somehow, sending the message that Williams owed it to all of us to stay alive because, otherwise, his death would traumatize a lot of people. It’s the “suicide is selfish” argument in other clothes. Keep yourself alive because other people will be hurt if you don’t.

My problem is that people struggling with suicide are already carrying a huge burden, and explicitly loading them down with the weight of duty and obligation to other people is unlikely to help. It’s likely to make things worse.

I don’t want to live in a world where Robin Williams owed it to us to stay alive. I think this kind of statement makes it harder for people with thoughts of suicide to ask for help because it sets up a duty/blame dynamic that gets in the way of supporting them. And, again, what does it gain us in our larger campaign to prevent suicide?

Media guidelines

We need to partner with media if we want to affect the course of reporting on suicide. Now that there are millions of blogs in addition to traditional media, this is a big job. We should expect that most journalists have never seen or heard of the media guidelines for reporting on suicide.

It’s ironic, perhaps, that Schmitz’s op-ed piece links to an American Association of Suicidology media guidelines page that doesn’t exist. In fact, I can’t find a single link to “media guidelines” anywhere on AAS’s main webpage. It’s there, if you mouse over “Resources” and then scroll down to “Recommendations for Reporting on Suicide”, but I missed it the first four times I went looking for it, and it’s not labelled “media guidelines”. If I were a reporter writing on a deadline, I’m pretty confident that I would have missed it and given up.

The tone of the statement, “clearly, not all professional journalists have read or follow the media guidelines regarding the reporting related to suicide and suicidality” feels reproachful. Yes, it’s true—most of them have neither seen nor followed the guidelines. But framing this in negative terms, by critiquing their past failures rather than asking them to partner with us in the future, buys us little but enmity.

Probably most journalists have never heard of our guidelines. They’re decent people, and I’d bet that most of them want to keep their readers alive (even if it’s just to keep buying papers). Let’s give them credit for good intentions and work with them to reframe the message, instead of criticizing their failure to follow the rules they didn’t know about.

In the end, I found the guidelines, at http://www.suicidology.org/Portals/14/docs/Resources/RecommendationsForReportingOnSuicide.pdf . That’s long and challenging to type, and it’s the sort of link that seems likely to break when the recommendations get updated. I’d like to propose two things: one, put a symlinked page at http://www.suicidology.org/media/ and another at http://www.suicidology.org/reporting/ that point to the current guidelines, and just redirect the link when the guidelines change.

Two, put a link to “Media Guidelines” in the topmost menu bar on every page of the AAS website, in the line that has Login and My AAS and Shopping Cart. Journalists are always going to be pressed for time, and we are more likely to get them to help us if we make it really easy to do. Don’t make them hunt for the guidelines. Make it easy.

Denying lived experience by calling treatments effective

I’ve heard so, so, so many people saying variants of this: “mental health treatments are effective“.

It’s true. Mostly.

A lot of the causes of suicidality are eminently treatable, whether by medication, therapy, or a combination. I know hundreds of people who’ve had episodes of thinking about suicide, have gotten treatment, and have found that the thoughts left and never returned. That’s FANTASTIC, and that’s what we want to hear. If people are struggling with thoughts of suicide, we want to drive them toward treatment, because it works really well for a lot of people. It’s a good bet.

But there are a lot of people for whom the treatments are not effective. I talk to callers who’ve been in intensive treatment for multiple decades and still aren’t better. They’re still here, still fighting to stay alive, but they’re not better. We deny their lived experience when we imply that treatment always works. For goodness sake, Robin Williams was receiving mental health treatment when he died.

I know people who’ve started treatment and found that it made them worse. Different medications affect people in different ways, and some antidepressants make depression worse, which is why medication management and active physician supervision is so important. Prescribing psychiatrists tell me that treating this stuff medically is challenging and complex. The outcomes are usually good, they say, but it takes work.

Many others have told me they went to a caregiver who had little experience with suicide and said hurtful or unhelpful things. Our own field frequently touts the assertion that most social workers and counselors in the US have had less than eight hours of training on suicide! We’re taught to use that statistic as part of how we encourage people to come to trainings on suicide intervention.

And, in any case, suicidal thoughts sometimes come back. Schmitz says “suicidal thoughts, by their very nature, tend to be time-limited — though they may regularly recur.” There’s hope in that, because we really can help people through the tough times, but also despair: treatment doesn’t always make thoughts of suicide go away forever. In this context, it’s reasonable to ask what “effective” means.

All of this leads back to my conclusion that making absolute blanket statements like “mental health treatments are effective” is unhelpful. It denies the lived experience of a significant group of vulnerable people for whom treatment has not helped that much, as well as silencing the experiences of their friends and families who’ve worked to support treatment that didn’t always do much.

Let’s encourage people to seek treatment. Let’s talk about how it can often help, and how medications or therapy help many—even most—people to survive their thoughts of suicide and never look back. But until we have treatments that always work, could we let go of the black-and-white encomia of treatment?

Conclusions

When highly-visible suicide deaths occur, we have a hard choice. We need to do our best to minimize the risk to vulnerable people, and that means encouraging them not to kill themselves. We also need to care for the people who are grieving for the suicide loss.

But much of our work on a national level falls more into the public health sphere than the individual intervention one. Given that, I think it’s important to talk about how our responses to suicide deaths gain or lose ground in the larger campaign against suicide.

Respectfully, I feel that a lot of what I saw coming out of the suicidology world after Robin Williams’s death backfired. I’ve talked about Schmitz’s article because it offered concise examples of things that worried me, but there have been many more articles and interviews. I don’t really want to talk about the specifics of any one article; I want to talk about how we can address these concerns next time.

Most of the points I’m making here came from people who’ve talked to me in the past two weeks, since I’m known in my community as “someone who knows about suicide”. I found myself left without answers for why our field responded in these ways, and I found myself working—particularly in regard to the Genie tweet—to comfort people who felt that they’d been shot down for sharing an image they thought would help.

So let’s talk about this stuff. We need lots of allies in this fight. Let’s show them what we hope they will do, praise them for doing it, and avoid shaming them.

(If you’re here because you’re struggling with thoughts of suicide, I hope you’ll consider reaching out for help. 1-800-273-TALK is free and confidential anywhere in the USA.)