Fears in a Hat: A Facilitator’s Guide

by Hollis Easter, (c) October 2013

Fears In A Hat is a good introductory team-building and group process exercise that gets people focused on good listening, encourages them to share vulnerability and build trust, promotes empathy for callers, and starts the process of forming groups and high-performing teams. It takes 20-60 minutes depending on group size and direction; it’s flexible enough to be taken in many directions.

I’ve been developing and adapting Fears In A Hat for a lot of years. It started as a team-building exercise that (I think) came to me from Coreen Bohl, and I’ve been shaping it into a crisis hotline facilitation activity ever since. At Reachout, we usually do Fears In A Hat at the end of our first hour of training, when new recruits are beginning to get to know each other and it’s time to encourage them to trust and open up a little more.

You can facilitate Fears In A Hat in lots of different directions; its simplicity and directness are part of its strength. It’s quick, cheap, and easy to set up. Trainees love it, too–most groups ask to do it again later in the training program.

We use it for talking about scary stuff in the past, but you could also use it in a classroom to get people talking about their fears of the subject (“What’s your biggest fear about math class?”), flip it to talk about hopes (“What are you desperately hoping to learn here?) or successes (“What are you most proud of achieving?”, “What do you wish everyone here appreciated about you?”). It’s a versatile exercise.

Structure and flow

Here’s what a typical Fears In A Hat session at Reachout’s Training Weekend might look like. I usually start it after a bunch of icebreakers, once the group has started to loosen up, and it’s the last thing we do before a break.

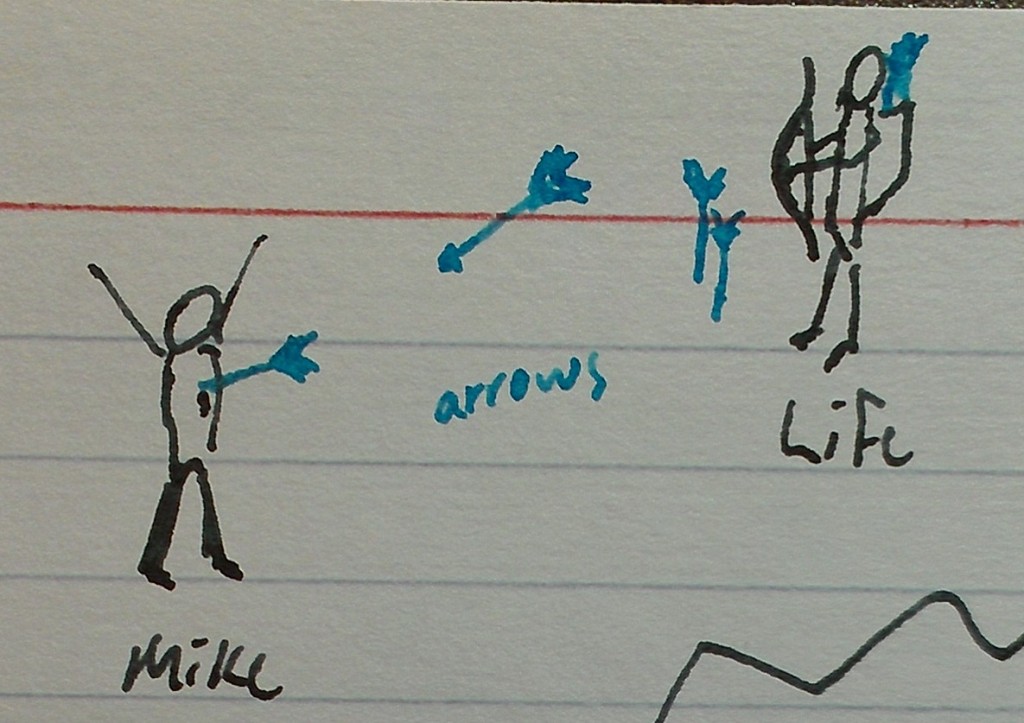

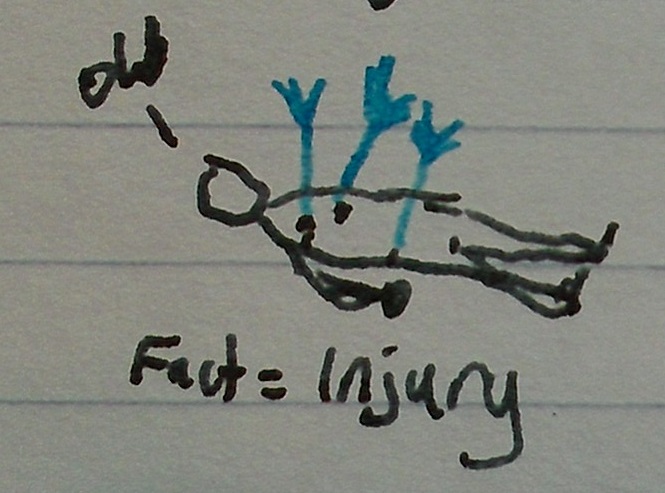

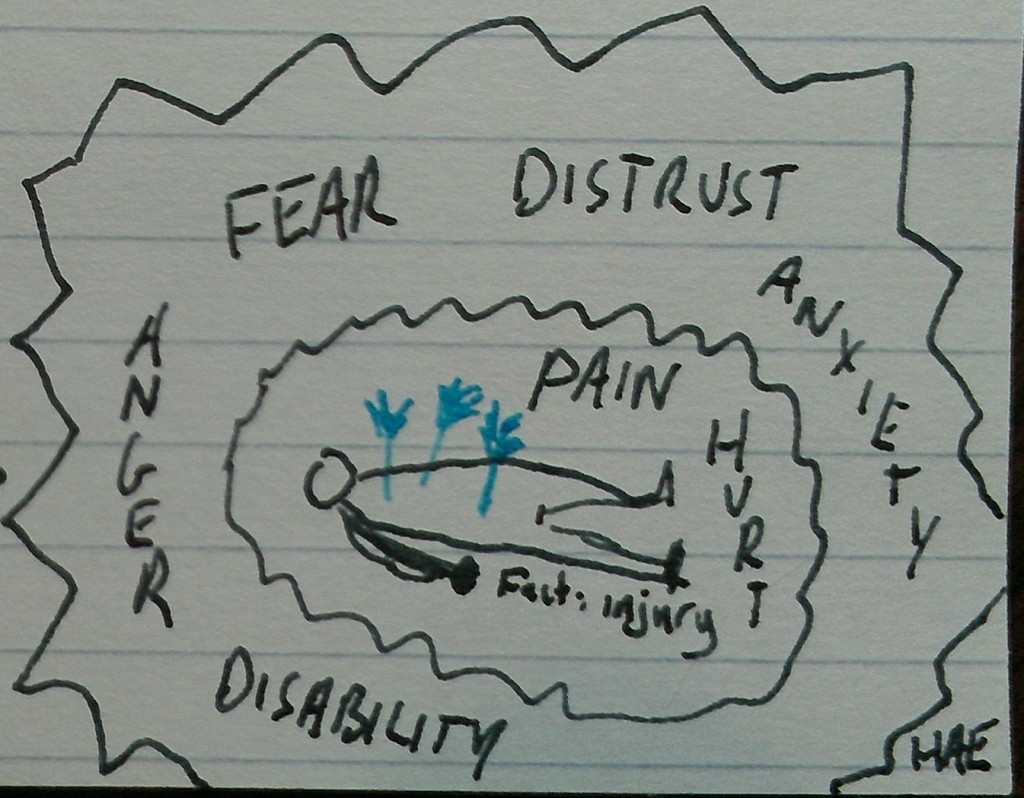

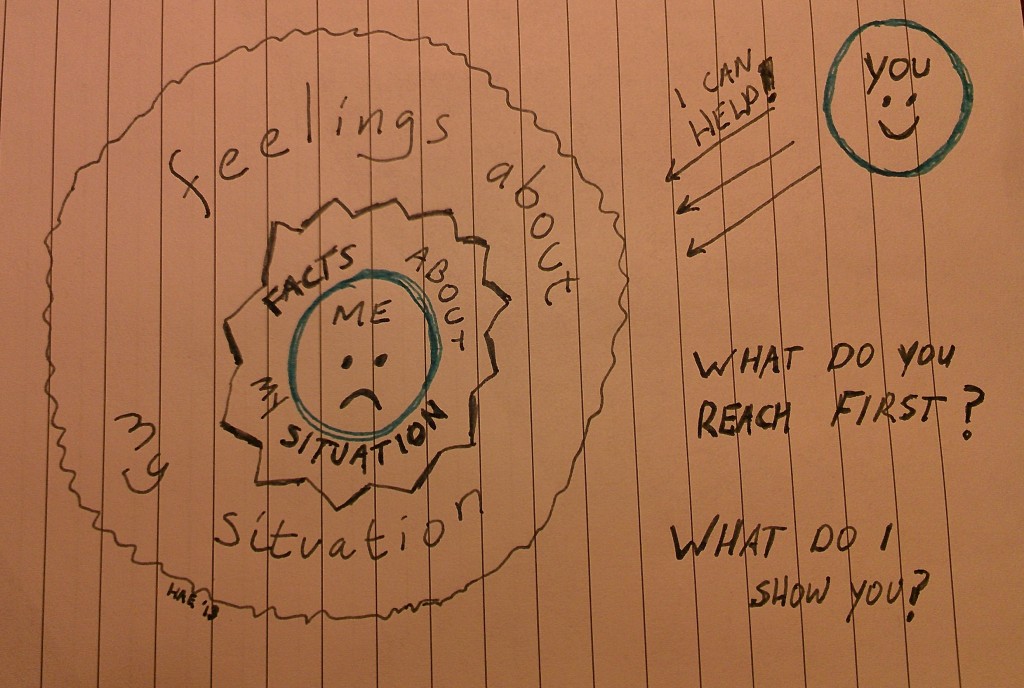

- Hollis: We’ve been talking a lot about communication styles, and I’m really encouraged by how you’re all thinking carefully and paying attention. That’s great, and I hope you’ll keep it up as the weekend progresses. But I’d like you to think about feelings, too. How do you think it feels to call a crisis hotline?

- Trainees: [usually say something like “uncomfortable” or “scary” or “worried”]

- Hollis: Yeah! It’s hard work to call people you don’t even know and ask them for help. We’ve talked about unconditional positive regard, but the callers also deserve our respect–asking for help like this isn’t always easy. Does that make sense?

- Trainees: [“Yes”, “yeah”, “mmhmm”]

- Hollis: It’s really important that we respect them for asking, and I’d like you to really imagine what they’re going through when they pick up the phone. To help you do that, we’re going to do another exercise right now–it’s called Fears In A Hat. I’ll pass around some index cards–would you all take one?

- [Hollis passes around the index cards and waits until everyone has one]

- Hollis: Okay. I’d like you to think for a moment about your own life, and think back to something that you’d feel really ashamed to have other people know was true about you. Maybe it’s something you did, or something that happened to you, or something you thought, or whatever… but think back until you’ve got something that would be really scary to share with others.

- Hollis: Everyone got one? Good. So here’s my challenge for you. Write it down on your card. I’m going to do it too. I want to give you a chance to feel what it’s like to open up about something personal, and I also want you to feel what it’s like to be heard and valued without judgment. I want this to be anonymous, so please don’t write your name down. Just write your scary thing on the card, fold it in half once, and put it into the hat on the floor in the middle of our circle. Once everyone does that, I’ll shuffle them and read them out loud. Before we get there, we’ll talk a bit about how you’d like me to read them and what we can do as a group to support everyone.

- Hollis: If that feels too hard, you’re welcome to make something up instead of using something that’s true. If you do that, please try to make it something reasonable–but I really encourage you to try writing something about yourself. We’ll do our best to support you–give it a chance. Once we’re done, I’ll tear up all the cards. Any questions?

- Trainees: [nothing]

- Hollis: Oh, and my eyesight isn’t perfect, so please write legibly, okay? [Trainees usually laugh.] Okay. Let’s all write.

- [Time passes. Once everyone’s done writing, Hollis gathers the cards from the hat.]

- Hollis: Okay… [while shuffling] How’s everyone feeling?

- Trainees: [usually someone says “I want my card back!” or “I feel scared!”. If not, I lead with something like “Probably kind of nervous, right?”]

- Hollis: So imagine that you’re hurting enough that you’re willing to call a crisis hotline about what’s on your card. Is this how you’d feel? Nervous? What are you nervous about?”

- Trainee A: You’re not going to respect me.

- Trainee B: You’re going to think I’m stupid for being upset.

- Trainee C: You’re going to laugh at me or not listen.

- Trainee D: You’re going to tell me I have to do something about it even though I don’t want to.

- Hollis: Yeah, exactly. You’ve got a lot of concerns about how I’m going to react–me, the hotline worker. So what do I need to do to put you at ease?

- Trainees: [think for a while]. “Sound nice.” “Don’t rush into it.” “Let me talk, don’t push me.” “Don’t make me feel like my problems are the worst things you’ve ever heard.” “Be respectful.”

- Hollis: Okay, good. So for this exercise, where I’m just reading your card, what do I need to do to sound respectful and nice?

- Trainees: “Go slow but not too slow”. “Don’t use a lot of inflection”. “Yeah, but don’t talk in a monotone either.” “Try to sound kind.” “Don’t add anything except what’s on the card.”

- Hollis: Okay, I think I can do that. What should you do, as listeners in the circle, to make sure everyone feels supported in the group?

- Trainees: “Not make eye contact.” “Not try to figure out who goes with what card”. “We should look at the cards so we can’t see people’s handwriting.” “I don’t want people noticing when I’m blushing or crying”.

- Hollis: Okay. How about keeping our eyes on the floor in the center of the circle. Does that work? [Trainees nod.] Can we all agree to stay in the circle until I’m done reading them all, and agree to keep the stories confidential within this group? [Trainees nod.] Okay. Remember to support your peers when you’re hearing their stories, and to notice how it feels when we’re hearing yours.

- [I then take a card from the stack, read it slowly and without much inflection, pause after finishing, then deliberately tear the index card into pieces–at least three tears, with a slight pause between them.]

- [Repeat this for all the cards in the stack, including my own. Small pause.]

- Hollis: Thank you. [pause]. Thank you for doing that, and for trusting us. Before we go on, I just want to start with this: whichever story was yours, whichever thing you wrote, you’re welcome here.

- Hollis: How are you feeling?

- Trainees: “I’ve never told anyone that.” “Relieved.” “I forgot which one was mine.” “I feel better about it.” “I’m glad that’s over.”

- Hollis: How did I do on reading the cards?

- Trainees: “Great.” “I’m glad you didn’t do anything dramatic.” “It felt good.”

- Hollis: How did we do at listening and supporting you?

- Trainees: “Good.” “I was so aware of everyone else when it was my card!” “I got really fascinated by some of the stories.” “I never knew silence could be so helpful.”

- Hollis: I hope you’ll remember these feelings throughout the weekend and throughout your time taking calls. Remember that the callers are taking a big risk sharing with us, and that they deserve our respect–and remember how good it feels to be heard.

- Hollis: We’re going to take a 15 minute break now. We’ve got some snacks in the other room… everyone thumbs-up? [That’s our signal for “doing okay”. They give thumbs up.] Okay. I’ll stay in here for a bit in case anyone needs to talk. See you in 15 minutes!

In most groups, depending on how much people have to say at the end, Fears In A Hat takes between 15 and 40 minutes. I’ve had it take a full 60 minutes once, because we got into a really good discussion about what it felt like to share personal stories and I didn’t want to interrupt. In years of facilitating it, I’ve never seen this exercise flop.

Purpose

Fears In A Hat can have a lot of purposes, depending on your environment, your learners, and your facilitation style. Here are some of our purposes in using it.

- Promote group formation at the beginning of a three-day training conference.

- Create a shared experience to use as fodder in later workshops.

- Give trainees with heavy stories a chance to share the burden with others and, by doing so, become more open to training.

- Gauge the group’s composition: are their Fears similar or different? Are some really involved while others are simpler, or is it more homogeneous?

- Build trust that, while we will ask them to do scary things in training, we will also always support them.

- Get them out of their heads and into their emotions to prevent them from intellectualizing problems too much.

- To encourage them to respect the work callers do in asking for help.

- To remind them that we, as a group, are no different from our callers.

Materials/environment

- Index cards (at least one per person)

- Pens/pencils (one per person)

- Hat or basket to use for collecting the index cards (optional)

- Wastebasket for ripped cards

It’s important that all the chairs be in a circle for this exercise, including the presenter’s chair. The circle keeps people from sitting in the back or feeling like others are staring at them. If you’re using a hat, place it on the floor in the center of the circle.

It is absolutely critical that everyone in the room participate. We often have other hotline staff observing our trainings, and if there are observers in the room, I lead into the exercise by saying “I’d like everyone in the room to participate, so everyone feels safe. Would you be willing to come sit in the circle and write with us, or would you rather sit in the other room for a while?”.

The last time I did Fears In A Hat, our executive director walked in during the exercise to check on a detail for the next session. I paused the exercise, answered her question, and then explained that we were in the middle of Fears In A Hat and asked her to either take a card and write a fear or step out of the room. I think it’s important that these conversations be matter-of-fact and audible–because, in the eyes of the trainees, you’re defending their safety. Everyone in the room participates.

Key points

Most of these key points have to do with safety and challenge. We’re asking trainees to do something that’s a little frightening and perhaps a little dangerous–which is good, because it’s a challenge that will help them to grow. But we need to make sure that we assiduously guard their safety, too.

- Confidentiality and respect. Make sure everyone understands the expectations: that this information stays within the group; that people’s responses are confidential; and that we are practicing listening respectfully, no matter what comes.

- Everyone participates. No exceptions. I offer them the chance to make something up as a way to make sure everyone participates, although I strongly encourage people to try it with a real story. But if someone can’t even participate under those circumstances, ask them to leave the room until the exercise is over.

- Allow escape valves. I usually invite people to sit, or stand, or sit on the floor, to make sure they’re comfortable. They need to stay with the group, but I often invite them to move around if they need to. I also try to let them know that we’ll have a break after the exercise, so they can pull themselves together if they need to.

- Who touches the cards? I’m the only one who touches the cards once anyone has written on them. This is a safety piece.

- No detective work. Ask for, and get, a commitment not to try to figure out which story belonged to each person. Again, this is a safety piece.

- Guide their practice and attention. Early in training, people don’t necessarily think of listening as an activity that involves specific behaviors. Guide their attention to how they listen, and to how they feel, so they’ll have a chance to notice and then talk about them.

- Give clear instructions. Clear handwriting, no name on the card, fold it once and put it in the hat.

- Destroy the cards ritually. Rip them several times each, and do them right away instead of waiting until the end. Many participants have told me this is the most spiritually important moment of the entire first day of training.

- Allow time for process. People may want to talk about their feelings. If you’re comfortable facilitating, you can leave this pretty open-ended; if not, or if you’re pressed for time, you can guide their reflections toward how it felt to listen, to be heard, to hear the cards being torn up, etc.

Wrap up

Listening is important for good hotline work. Most of us are here because we want to help callers, but lots of hotline folks came to the work because we felt that others didn’t listen to us. We have a pretty deep need to be heard, but we often feel that we shouldn’t need it, don’t deserve it, or won’t ever have a chance to tell our stories. Like the callers, we jump at the chance to tell our stories and feel supported. That’s part of why Fears In A Hat works so well: it’s satisfying a need in the learners while teaching them and giving them a chance to practice.

You can take the exercise in lots of directions. It works as an icebreaker, as a team building exercise later in training, as group formation, etc. As long as you commit to the open, respectful process and enforce the safety rules, it’s pretty much no-fail. You can use it again later in training to get trainees to notice what’s changed since they started learning to listen.

I encourage you to try it! If you have questions, please leave a comment asking them!

If you enjoyed this post, you might also enjoy reading: